This story appears in the current issue of Forbes and was reported jointly with Ryan Mac in San Francisco. To find out more about Lei Jun’s wealth, check out this post by Ryan.

Lei Jun is selling millions of groundbreaking smartphones--and attracting a cultlike following.

There aren’t many American entrepreneurs who would have the nerve to compare themselves to Steve Jobs and Apple. To find a guy crazy enough to do that, you have to go to China.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet Lei Jun, the jeans-and-black-shirt-wearing billionaire founder of Xiaomi, China’s hottest smartphone company. And, if you believe Lei, the next Steve Jobs.

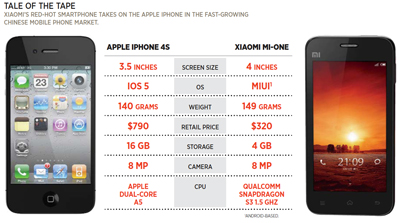

Beijing-based Xiaomi sells an Android smartphone called the MI-One. It’s a high-powered phone based on a dual-core processor from Qualcomm but with a price far lower than many comparably equipped phones sold in China. That combination of raw power and a reasonable price tag has attracted huge attention from Chinese consumers: When the phone went on sale last fall, Xiaomi received 300,000 preorders in the first 34 hours. Less than a year after launch the company has sold more than 3 million MI-Ones and counting. The phone is hot. Red-hot. Apple hot.

Lei, a 43-year-old investor and serial entrepreneur, is the public face of Xiaomi. Like Jobs, he has intense loyal fans—mostly young, male gadget hounds. The company launched an annual convention for fans and holds regular user meet-ups that have the feel of religious revivals, where diehard fans sing, cheer and play games. Lei has more than 4 million microblog followers in China and spends hours on MiTalk, the Xiaomi chat site, to solicit feedback from users.

In his first big score, Lei sold the online retailer Joyo.com to Amazon in 2004 for $75 million. Three years later he listed Kingsoft, an antivirus software firm, on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (for more on Kingsoft see this interview by Laura He with its CEO). He’s an investor in both UC Web, which sells a popular mobile browser, and YY.com, which offers a real-time video app.

Lei founded Xiaomi in 2010 with his friend Lin Bin, a former Microsoft and Google engineer who is now Xiaomi’s president. The two men, both 43, both married with daughters (Lin has three, Lei two), had spent the previous months dreaming of a high-spec, low-price phone.

Their big idea is to subsidize the cost of the handset by getting buyers to pay more for various services—not unlike the way that Apple iPhone users pay for software from the App Store.

It’s just one more way the company keeps inviting comparisons with Apple. Lei has a love-hate relationship when it comes to the comparison. He says Jobs is an inspiration but specifically denies, for instance, copying his dress code, asserting that his casual attire for product launches is simply a plug for his Vancl fashion e-commerce site.

“I was annoyed in the beginning, very annoyed. But I don’t mind anymore,” he says of the comparisons. Associates say he gets a kick out of being dubbed Lei-bu-si, a pun on Qiao-bu-si, Jobs’ Chinese name.

Rather remarkably, Lei risks the wrath of Apple fans everywhere by asserting that he can succeed in China in ways that Jobs never could have matched.

“If Jobs had lived in China, I think he could not have succeeded,” Lei said in an interview with FORBES. “Jobs was a scrupulous perfectionist, while Chinese culture emphasizes the middle path.” In China, he says, “you also need to make compromises.” That’s a lesson that American companies have had trouble learning: Witness Google’s departure from mainland China in the face of persistent censorship of search results.

One thing is for sure: In China the guy produces Jobs-like buzz. The rapid early sales of the phone came largely through word of mouth, with no spending on print or TV ads. And the buzz continues: After selling 3 million phones to date, Xiaomi is on track to hit 5 million to 6 million units by year-end.

Part of the mythology around Lei involves a highly public spat he’s having with Zhou Hongyi, the CEO of Nasdaq-listed Qihoo 360 Technology, a $1.9 billion market cap security-software firm. For one thing, Zhou claims that Xiaomi makes a profit of nearly $100 per phone, disputing Lei’s assertion that it sells the phone cheaply and will make up the difference with services. Zhou thinks Xiaomi’s customers are suckers if they believe Lei.

Another source of friction: Zhou leaked the news that Xiaomi’s latest round gave the company a $4 billion valuation. While the number was accurate, Lei says, the leak made it harder to close the deal with privacy-sensitive investors.

Tied into the feud is the fact that Qihoo competes with Lei’s Kingsoft in the antivirus PC-software market. Qihoo has been giving away a free version of its antivirus software for users who download the company’s browser, a move that creates issues for Kingsoft.

Even Lei’s detractors would concede that the opportunity here is enormous. China Mobile is the largest mobile carrier in the world, with 677 million users as of the end of May; compare that with AT&T with a little over 100 million as of the end of March. The number two and three carriers in China—China Telecom and China Unicom—also are bigger than any U.S. carrier.

Moreover, Chinese consumers are moving rapidly to embrace smartphones. Over half of all mobile phones sold this year in China will be smartphones, rising to 76% next year, according to Nomura. Topeka Capital Markets says there will be 230 million 3G users in China by year-end.

To be sure, Xiaomi is still small compared with its better-known rivals. In Q2 smartphone shipments in China were 33.1 million units. For the full year China smartphone shipments should hit 140 million, which would put Xiaomi’s share at less than 5%.

But there is plenty of room for expansion—both inside China and elsewhere. One obvious lure: Xiaomi’s phone at $320 is priced far below the $790 local price for the Apple iPhone 4S.

Even so, the challenges are daunting, even for larger players. Nokia, Research In Motion and HTC are struggling to stay relevant in a market dominated by Apple and Samsung. Xiaomi is trying to steer a middle course between high-end rivals on the one hand and cheap-as-possible mobile devices on the other.

Meanwhile, Lei is getting rich.

In June Xiaomi raised $216 million in venture capital, the round that valued the company at $4 billion. That’s more than the current market cap of Research In Motion. The latest round boosts total capital invested in Xiaomi to over $500 million.

Investors include Morningside Group, Qiming Venture Partners, IDG, Temasek and DST Group founder Yuri Milner. Lei remains the largest Xiaomi investor, with a stake of more than 30%, sources say. Ergo, he’s a billionaire.

To stay in the billionaire’s club, Lei is going to have to maintain both the zealous consumer support for the company’s phones and his own cult of personality. The constant comparisons with Steve Jobs, which might not play well here, work to his advantage in the domestic China market.

“In a culture like China, we feel the need to have our own Jobs,” says Wen Chu, CEO of Great Wall Club, a Lei-funded trade group. “We want to see him succeed.”

That will not be easy.

“It will be incredibly challenging for Xiaomi to execute an Apple model in China,” says Michael Clendenin, managing director of RedTech Advisors, a Shanghai-based consultancy. “As much as I admire Lei Jun, he’s no Steve Jobs when it comes to developing an ecosystem.”

The long-term goal is to follow in the footsteps of China-based hardware makers Huawei and ZTE and to enter the global market.

The company’s ability to move beyond China will be tested when Xiaomi makes its first move overseas next year. Lin Bin says he’s talked to carriers like Telefónica and Vodafone but that no deals have been signed to date. In China Xiaomi has distribution deals with carriers but sells about two-thirds of its phones direct via Xiaomi’s website.

Hans Tung, a partner in Qiming Venture Partners, notes that if Xiaomi hits annual sales of 6 million units, it would be approaching $2 billion in annual revenue.

But sustaining that growth will be a challenge. What looked like a sweet spot in 2011 is becoming a maelstrom of competing handsets. The price of a “good-enough” Android or Windows smartphone is down to just $100, with lower prices ahead.

“The payoff is enormous, but margins start to become very thin,” says Mark Natkin, managing director of Marbridge Consulting in Beijing.

Lei insists that competition from smartphone discounting doesn’t hurt him. “We never planned to make a profit from hardware … so a price war will not affect me at all.” A brave statement but clearly not true; there’s no getting around the fact that the company is hurt by lower prices, just like everyone else.

To hold its ground Xiaomi needs to retain the loyalty of users like Zhang Jie, a 24-year-old magazine editor. Zhang says he chose the phone for its impressive specs and describes its operating system as “cool and comfortable to use.” But he hasn’t spent anything on apps and says that if he had the money he’d switch to an iPhone.

Clearly, Xiaomi has a long way to go before it can compete head-to-head with the company Steve Jobs built. Lei is convinced that over time he can get there. Give him credit for thinking different.

“Apple is a great company,” he says. If you believe Lei, Xiaomi might take it one step further.